|

|

This item is a certified AUTHENTIC Dutch Doit recovered from the sunken

vessel Bredenhof. The Bredenhof, en route to India, sunk off the coat of Mozambique on

June 6, 1753. Munt komt uit 1755, als ik goed lees, en kan dan niet van de Bredenhof komen. US $20,00 (EUR 15,95), 28-aug-06, ebay, levs2001 |

|

Netherlands Indies, VOC Duit, Zeeland 1752, Bredenhof wreck "This coin was recovered from the Dutch East India Company vessel Bredenhof, wrecked on June 6th 1753 in the Mocambique Channel. Date of Salvage June 1986." 2,79 gram, 22,19 mm, 22,12 mm US $21,00 (EUR 14,14) BeŽindigd: 25-jan-08, ebay, davis471 |

http://www.vocshipwrecks.nl/out_voyages8/bredenhof.html

VOYAGE NR: 3582.3

NAME OF VESSEL: Bredenhof

The Dutch East India Company, commonly called the V.O.C. (Vereenigde Oostindische

Compagnie), sent out hundreds of ships in the 17th and 18th Century to trade in the East.

This giant conglomerate despatched vast fortunes in silver and gold arount the African

continent and through the perilous Indian Ocean to the Company's headquarters in Batavia.

The V.O.C. was divided into six Chambers: Amsterdam, Rotterdam, Middelburg, Delft, Hoorn

and Enkhuizen.

In September 1752 the Dutch Council of Seventeen of the V.O.C. ordered the Chamber of Middelburg to send the BREDENHOF via Ceylon to Bengal. The BREDENHOF, built in 1746 was a vessel of 136 feet and 800 ton. The voyage to Bengal would be the third and last of the BREDENHOF to the East Indies. In the year 1752 the Chamber of Middelburg not only lost the WAPEN VAN HOORN, but also the famous GELDERMALSEN. In the year 1753 the Chamber would suffer another loss: the BREDENHOF.

The ships KASTEEL VAN TILBURG and ZUIDERBURG of the Chamber Amsterdam were also sent to Bengal. The three ships left Holland at seperate times, carrying with them bar silver, gold ducats and copper 'Duiten' to the value of 1.100.000 guilders. This specie was split among the three ships. The BREDENHOF's cargo manifest was listed as 14 'vaatjes' with copper 'Duiten' and 30 chests with silver and gold. This was made up to 29 chests of bar silver, valued at 300.000 guilders, and one chest with 5.000 gold ducats, valued at 25.000 guilders. The silver was set apart for Bengal to be minted into silver Rupees.

The BREDENHOF sailed from Zeeland on 31 December 1752 and arrived at the Cape on 11 April 1753. Of the 260 men on board of the ship, six were dead and nine were sick. At the Cape the BREDENHOF loaded 38 tons of wheat and some wine for Ceylon. Two weeks later she sailed from the Cape, but did not reach the port of destination.

In calm conditions, but as a result of treacherous counter currents, the BREDENHOF was wrecked on a reef 13 miles from the east coast of Africa and about 120 miles south of Mocambique, the Portuguese settlement on the African coast. This tragedy took place on 6 June 1753. The story became quite fascinating when, out of desperation, the Captain and Ship's Council decided to throw overboard the vast fortune in bar silver, to eliminate plundering by the rest of the crew and by 'other nations'. One can imagine the concern shown by the Dutch Council of Seventeen when the first survivors arrived back in Holland, and told them of this dreadful story. It is evident that the Council was desperate to salvage as much as possible of the bar silver.

Whilst interviewing two survivors from the wreck the Council was told of the utter desperation the crew faced. In the early hours of the morning of 6 June the ship drifted on a dangerous reef. To lighten the ship they jettisoned some cargo, ballast and lastly the cannons overboard. This was still not enough. They then set out the life-boat and barge to drop the two anchors and tried to winch the ship off the reef. The despair was complete when the anchors parted and the boat and barge drifted ashore. They were then left to the mercy of the elements. A gale was blowing from the south-east and the waves were breaking right over the ship.

On 8 June the Quartermaster left with 20 others on the life-boat and sailed to shore. On 11 June the ship started breaking up. At that moment the Captain and Ships Council decided to throw overboard 14 chests of silver through a hole made by a ruddertrunk in the stern. They did not mark the spot with any buoys, as the chests lay in three fathoms of water and could be seen quite easily from the surface. The boat returned to the BREDENHOF to collect some of the crew. Pieter Bakker, the first mate, and two sailors managed to swim through monstrous waves and were picked up by a boat. After another abortive attempt to rescue some of the crew, the life-boat sailed to the Commore Islands in the Mozambique Channel.

The Captain and the rest of the crew made rafts and sailed to shore. He carried with

him the gold ducats in five bags. On shore they found the barge, which had run aground.

They also found the Quartermaster, murdered on the beach. Later, one of the bags was

stolen, but most of it was recovered. In three seperate groups, less than 200 men started

making their way northwards towards Mocambique. Two and a half months later they arrived

at the settlement having suffered heavy casualties. Half of the men died on this difficult

journey. Four survivors of the BREDENHOF went back to the reef where the ship wrecked, but

could not see anything of the vessel any longer.

In the Portuguese fort of Mocambique, Captain Jan Nielsen of the wrecked BREDENHOF placed the gold ducats in safe custody with the Portuguese Governor. The survivors managed to catch a lift on Portuguese ships to Brazil and then on to Holland. Captain Nielsen, died as the ST. FRANCISCUS, on which he sailed as a passenger, approached the southern tip of Africa, Cape Agulhas. Before he died he gave the logbook of the BREDENHOF to Pieter Roosenauw and Pieter Williamszoon. It was these two men, who suffered such terrible hardships, who reported to the 'Council of Seventeen'.

The group with the first mate Pieter Bakker, managed to get a lift on the Swedish ship

PRINS KAREL from the Commore Islands to Surat in India. In January 1754 the JONGE SUZANNA

was sent from Surat to Mozambique to collect crew members of the BREDENHOF and to see if

any of the chests with silver could be salvaged. Pieter Bakker was sent back on the JONGE

SUZANNA to show the way and to point out where the precious chests with silver were.This

salvage vessel arrived at the scene of the wreck on 5 March 1754, eight months after the

tragic event.A day before, they met a Portuguese vessel, whose captain informed them that

their trip was in vain as other Portuguese ships had already searched for the BREDENHOF

and now nothing of the wreck could be seen. In spite of this information they sent out a

small boat to search the reef. The sea was exceptionally clear and they could see

everything on the bottom. They saw an anchor and some cannons, but no sign of the chests

with silver.They suspected that everything recoverable, including the silver bars, must

have been salvaged.

They looked no further and made their way to Mozambique to collect the survivors of the

BREDENHOF. In Mozambique they heard that the survivors already sailed with Portuguese

ships to Brazil. The JONGE SUZANNA sailed back to Surat where she arrived in June 1754.

The first survivors of the BREDENHOF arrived in Holland in June 1754. The 'Heren XVII' were unaware of the salvage expedition of the JONGE SUZANNA from Surat. The council decided to sent a second salvage vessel from the Cape, especially to recover as much of the silver bars as possible. The instructions to the captain of the SCHUILENBURG were to proceed with the first favourable winds to the site of the wrecking of the BREDENHOF and to bring up the chests of silver, cannons and anchors. If he was able to salvage at least two or more chests he was to sail to the Cape.

If he found less than that he was to sail to Madagascar and trade for slaves. On 22 April 1755, almost two years after the wrecking of the BREDENHOF, the SCHUILENBURG left the Dutch settlement at Cape Town. There was already considerable confusion as to where the ship went down. According to the instruction they were to sail to Latitude 20 degrees 10'. This was 200 miles south of the site where the BREDENHOF had gone down.

On board were Pieter Roosengauw and Jonaszoon, two survivors from the BREDENHOF who were sent to the Cape for this salvage expedition. When the SCHUILENBURG arrived at the Latitude indicated they informed the captain that this was the wrong area. Having spent a considerable amount of time in the vain search for the wreck, they sailed northwards to Mocambique. There they heard many stories about the BREDENHOF. They interviewed some Portuguese captains and found them evasive. They also noted that the Portuguese charts of the area greatly differed from their charts.

The Portuguese accused the natives of salvaging and stealing the silver bars. They implied also that the first salvage expedition from Surat recovered four chests of silver and the great anchor. The Ships Council of the SCHUILENBURG suspected that both the natives and the Portuguese had brought up everything of value. Having heard of the salvage expedition of the JONGE SUZANNA they decided that a longer stay at the coast of Mocambique was unnecessary. They continued to Madagascar and succesfully traded for slaves. The SCHUILENBURG eventually arrived back at the Cape on 17 January 1756 and a detailled report of the unsuccesful salvage expedition was sent to the Council of Seventeen in Holland.

More than two centuries later, a Cayman Islands company contracted with Captain Klaar to set out and salvage the BREDENHOF. The team set out on a Chinese Junk, the MARIE JOSE, on 29 May 1986, having carried out extensive research. They were greatly troubled by the confusion surrounding the incident and the accusations made about the subsequent salvage attempts. However, they felt sure that there was still a chance of finding some silver lying amongst the bones of the wreck.

They decided to survey all of the offshore reefs in the area. After checking one area and having found nothing, they moved off to the next likely area and, within a very short period, nearly had to abandon the entire expedition. 'We had been using a sophisticated magnetometer, which is able to detect ferrous metals underwater, when a huge wave appeared out of nowhere. The wave tilted the inflatable boat, threw all of us overboard, and completely swamped the boat. We all feared for our expensive electronic equipment and managed to climb on board again and inch our way out of the dangerous swells. Fortunately we were able to save and salvage most of our equipment and we were able to restore it again to working condition.'

'The very next day we received a signal from our magnetometer. The water unfortunately was far too dirty to see anything on the bottom and we had to wait another three days before the water cleared. Within 10 minutes of entering the water the first shriek of victory was heard. Tommy, one of the divers, found a small sliver of silver in the middle shallow sandy gulley lying there, all by itself, for over 200 years. Nothing else was found in this immediate vicinity, but we knew we were on the right track.'

A short while later they found a small anchor and, the biggest surprise of all, hundreds of silver ingots lying on top of large flat rocks and in shallow sandy gulleys. A short distance away a huge block of silver ingots fused together and weighing over 120 kilos. A little further another chest of silver with 50 ingots fused together.

'We lay down a grid of bright yellow rope and started surveying and charting the area. We were being plagued by dirty water and very strong currents: The tidal difference is 3 to 4 meters. We found another cannon and a large quantity of copper coins, 'Duiten', all marked 1752 and from the Zeeland mint scattered all over the place. A few blocks of iron pig ballast were found, some lead sounding weights and a pewter plate lying next to one of the cannons. We were now worried about the lack of cannons in the area and, what about the anchors that had been thrown off to enable the survivors to winch the stricken vessel out of their perilous position?'

They continued surveying the area and 5 days later and 15 miles away were able to complete the story on the BREDENHOF. They received another reading from the magnetometer, went down and found a big clump of 13 iron cannons lying in a depression in the reef. It was obvious that, once the BREDENHOF was trapped in the crater on the reef, no amount of winching could get her off. A little further out to sea they found the main anchor broken at the stem. This was a very strange sight especially when one considers how particular the early Dutch were in constructing of ships and anchors; this anchor should not have broken. The Dutch used to test the strength of a newly forged anchor by hoisting it up with a block and tackle and dropping it on a cannon. Unless the anchor survived the exercise without a crack, it would no be sent out on sea.

They found more copper 'Duiten' marked 1752 as well as some iron pig ballast blocks.

'We searched the area thoroughly and no silver ingots were found. It made us wonder who it

was that was able to salvage the chests soon after the wrecking. Was it the natives who

were able to dive down and pick up the silver or was it the Portuguese captains who

plundered the wreck? One thing is for sure, part of the wreck drifted off and snagged 15

miles away and our modern day salvage team was able to pick up part of the silver cargo

and copper coins. We intend going back to the area completing the excavation of the wreck

BREDENHOF.'

Bibliography and Sources:

Bruijn, J.R., Gaastra, F.S., SchŲffer, I. Dutch-Asiatic Shipping In The 17th and 18th Centuries (3 Vols). The Hague, 1979, 1987

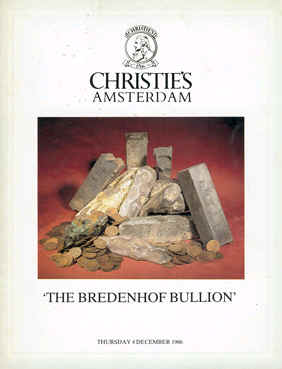

Christie's Amsterdam B.V. 'The Bredenhof Bullion'. 542 Silver bars, most stamped with

VOC markings, salvaged this year from the wreck of the 'Bredenhof', which went down in

1753 in the Mozambique Channel. Amsterdam, 1986